Our PhD students have organised a retreat for a couple of days, and as part of the festivities, they asked me to come up with a medical physics themed quiz round. Clearly my previous quiz round on how famous scientists died has become legendary. Their request came during a series of conversations I’d had with different people on the problems faced by women in science and how we can overcome them. So in the hope of initiating a conversation about a serious subject in a lighthearted way, I came up with ten quiz questions on women in medical physics. As usual, I try not to distinguish between “medical physics” and “biomedical engineering”, and use the terms interchangeably. The questions start easy, and very quickly get hard, in the hope of raising an important issue rather than testing knowledge. Here are the questions and a commentary on them:

Question 1: Who discovered radium?

This is of course an easy one. The answer is the go-to Woman In Science, Marie Curie, who I think can be claimed as an honorary medical physicist because she’s so famous everyone tries to claim her. I write this, incidentally, on the anniversary of her birthday. Happy birthday Marie!

Question 2: Edith Stoney has been called the first female medical physicist. Which decade was she appointed to the Royal Free Hospital as medical electrician?

I got this from the excellent series of historical articles which Francis Duck has written for the IPEM newsletter Scope, specifically “Edith Stoney, the first woman medical physicist” . Hers is a remarkable story. She had achieved a first class degree from Cambridge which was never awarded as women were excluded; she and her sister (a radiologist) went on to set up an all-female x-ray unit in the First World War after being refused permission by the War Office and pioneered wartime use of x-radiography. Coincidentally, Lise Meitner (a physicist who contributed to the discovery of nuclear fusion) also worked as a radiographer in the First World War, though on the German side. Even more coincidentally, Lisa Meitner shares Marie Curie’s birthday (Frohliche Geburtstag, Lise!)

The answer to the quiz question is 1900-1910. Edith Stoney was appointed part-time medical electrician to the Royal Free Hospital in 1901, after having been a general physics lecturer since 1899.

Question 3: Who was the first medical physicist to win a Nobel Prize?

This is tricky and I didn’t know the answer. I was looking up the usual UK triumvirate of medical physics Nobel Prize winners (Hounsfield, Mansfield and Rotblat; Rotblat being the odd one out in pub quizzes because he was the only one who describes himself as a medical physicist and he got his for Peace rather than Physiology or Medicine). But there’s another. Rosalyn Yalow got the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1977. I hadn’t heard of her. She was an American medical physicist who worked in nuclear medicine and developed the radioimmunoassay technique, now used to measure concentrations of radioactively labelled antigens in blood. Perhaps that’s more radiochemistry, but because she worked in medical uses of radioisotopes, I think we can claim her.

Question 4: Who provided x-ray diffraction images of DNA to Watson and Crick but died before they were awarded their Nobel Prize?

Rosalind Franklin. She was a chemist but a x-ray crystallographer working in DNA, hence the tenuous link to medical physics.

Question 5: In what film did Sandra Bullock play a biomedical engineer who got stranded in space?

Gravity. Yes. I know. I said they got tenuous.

Question 6: Who was the first female Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society?

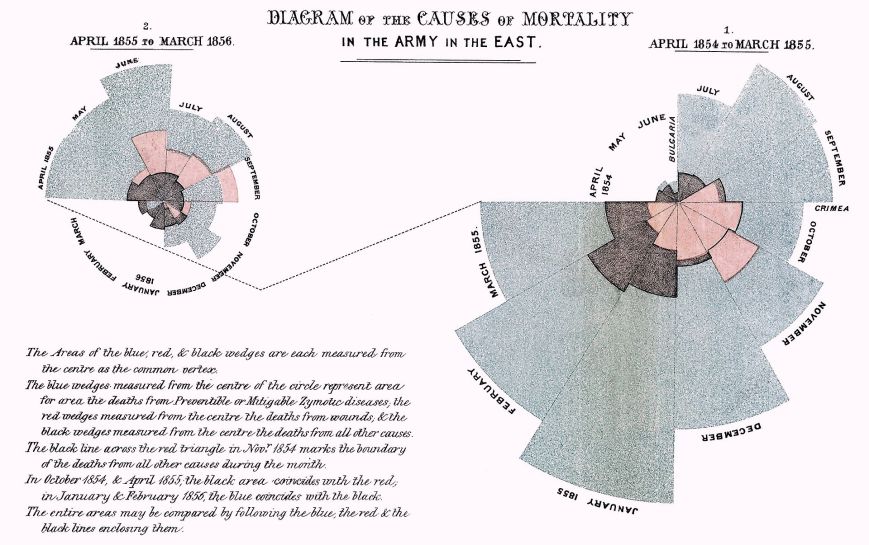

This is my all-time favourite pub quiz question. The first female Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society who invented the pie chart and pioneered graphical representation of data which she used in reports to Parliament on patient care in the Crimean War was only… Florence Nightingale! She also worked as a nurse.

There is a remarkable recording of her voice recorded on a wax cylinder which you can hear on her Wikipedia page. She’s also the only woman on my list to make it onto a ten pound note. And is of course a medical statistician and not really a medical physicist at all.

Here is her rather beautiful pie chart.

Question 7: What year did women win all five student prizes in UCL Medical Physics and Bioengineering?

A UCL question for UCL students, but in 2013, all five of our student prizes were won by women (2 undergrad, 2 MSc and one PhD prize). Hurray!

Question 8: In the UK, what proportion of physics PhD students are women? What proportion of physics lecturers are women? What proportion of physics professors are women?

Getting serious now. According to the Institute of Physics “Academic physics staff in UK higher education institutions” report from 2013, 25% of physics PhD students were women, 17% of lecturers were women and only 7% of physics professors were women. This is the leaky pipeline in action. We know it exists, we know there are lots of reasons for it, we even claim to know some of the reasons, but we don’t seem to know what to do about it. I don’t know the equivalent statistics for medical physics and biomedical engineering specifically. Certainly the undergraduate intake is about 50% female, which is a lot more than in physics in general. I suspect the pipe starts wider but is just as leaky. I don’t think I’ve seen a proper study on why recruitment into medical physics has a higher proportion of women than straight physics (and equivalently biomedical engineering has more women than other areas of engineering). The standard (and easy) argument is that it’s applied and more “caring” but that seems suspiciously easy to me.

Question 9: Put these countries into order from lowest to highest proportion of science researchers (not just physics and engineering) who are women: UK, Myanmar, Egypt

This fabulous map from SciDev.net shows the proportion of science researchers who are women. The commentary piece that goes with it is illuminating and points out some of the surprises. South East Asia and South America have the highest proportions of women in scientific research which looks great: what are they doing right? Thailand, Myanmar and Malaysia are all above or around 50% women, as are Venezuela, Argentina and Boliva. Western Europe clusters around 25-35% (the UK is fairly good here at 38%), but Eastern Europe is better, being mainly above 40%. Arabic speaking countries vary widely from Egypt (42%) down to Saudi Arabia (1.4%, the lowest in the world). Africa, similarly, varies widely with neighbouring and superficially similar countries being very different (Kenya 18% and Uganda 40%).

I guess this shows how complex the situation is internationally, and how difficult these data are to interpret. SciDev.net point out that a high proportion of women in research in some countries “may be due to working conditions being so poor that men avoid the sector”. What can we in the UK learn from this? I guess that the situation is complex (we know that already) and might be even more so in a large international university like UCL where students come from this wide range of backgrounds and may have varying expectations.

Question 10: In a peer-reviewed, gender-blind study in the USA, student CVs were anonymised, then randomly given male or female names and put to a job panel to decide what salary to offer. Men on the panel offered the imaginary male applicants $1200 more than the female applicants. How much more salary did women on the panel offer the male applicants?

This one’s probably a bit unfair as a quiz question but I couldn’t resist. It’s from what’s become a fairly well known paper with some surprising and worrying results:

C A Moss-Racusin et al (2012) “Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students” Social Sciences – Psychological and Cognitive Sciences 109 (41) 16474-16479

In this randomized double-blind study, academic scientists on a recruitment panel for a lab manager were given applications which were anonymised and then randomly allocated either male or female names. Panel members rated applications which appeared to come from male candidates as more competent and more hireable than identical applications which appeared to come from female candidates, and were more likely to offer the “male” candidates higher salaries and more mentoring. Curiously, interestingly and surprisingly, women on the panel discriminated similarly to men on the panel. Whatever the reasons for this, and different reasons have been put forward, it is certainly an issue which needs to be addressed. And clearly not by easy interventions like putting more women onto interview panels.

The answer to the quiz question, by the way, was about $2100: women on the panel appeared to penalise women applicants more than men on the panel did.

So this has been sitting on my computer for a week. The students should have had the quiz now so I can post it. I wonder how they went on?